As Genghis Khan nearly eight centuries ago, I leave Bukhara for Samarkand.

Samarkand’s birth and history follows a similar path to Bukhara. Both cities prosper along and from the Silk Road. Both become the capital of key political entities in Central Asia at different times. Though, their geographical proximity fuels also their economic and political rivalry for regional leadership.

After the fall of Bukhara in 1220, Genghis Khan and his Mongol army head to Samarkand, where his enemy the Emir Shah Muhammad, usually headquartered in Bukhara, has taken refuge. Following a short siege, Genghis Khan’s army defeats the 100,000 troops defending the city.

Samarkand pays a much higher price than Bukhara for its fierce military resistance to Genghis Khan. The defending soldiers who survived the battlefield are executed after their surrender. The civilians who had taken refuge in the citadel are slaughtered. The heads of the victims are piled up in pyramids outside the city to symbolise the Mongol victory. The city is razed.

Samarkand recovers only 150 years later, when the Mongol Timur (Tamerlane) chooses the city as capital of his Empire in 1370. Under Timur’s rule, Samarkand becomes the political, economic and cultural epicentre in Central Asia, while Bukhara suffers a corresponding decline.

Ruthless on the battlefield, Timur loves and patronises arts. He initiates an intensive reconstruction and beautification of Samarkand over the next decades – period known as ‘Timuran Renaissance’.

Samarkand owes much to Timur’s grandson Ulugbek as well. Less a ruler than a scientist and a poet, Ulugbek positions Samarkand as the intellectual centre in 15th-century Central Asia.

The pendulum swings again in the 16th century when the Uzbek Sheibanids establish their capital in Bukhara, which reduces correlatively Samarkand’s role and prosperity.

Registan

The Registan (‘Sandy place’ in Tajik language) constitutes the religious, intellectual and commercial centrepiece of medieval Samarkand. It consists in mainly three majestic and colourful madrasas disposed around a wide plaza, which hosted wide bazaar.

If you wish the Registan for yourself you better get up early and visit the place even before official opening hours. I enjoyed 30 minutes of smooth light, quietness and happiness before the crowds.

As Samarkand is razed by Genghis Khan’s army in 1220, the three main madrasas are built between the 15th and the 17th centuries. Thus, they count among the oldest preserved medieval Islamic schools in the world.

The Ulugbek madrasa is built in 1417-1420 by Ulugbek, Timur’s grandson. Ulugbek creates there a reputed centre of astronomical study. Renowned astronomers and mathematicians research and teach there, banking on the astronomic observatory built by Ulugbek in Samarkand. Brilliant astronomer, Ulugbek is a much less successful political ruler. He is beheaded by his oldest son while on his way to Mecca in 1449.

The other two madrasas are built much later on 17th century by a Sheibanid ruler, based on Ulugbek madrasa. Leaving you to discover the Sher-Dor madrasa, I do not resist sketching hereafter the Tilla-Kori madrasa.

Tilla-Kori (‘gold-covered’) medieval madrasa was added its outer dome during Soviet restoration work in 20th century. I enjoy much the serenity of the inner court, until the flame burning in the madrasa main hall. Once inside the building, I cannot detach my sight from the beautifully gold-plated ceiling of the main hall.

The madrasa displays nowadays a beautiful collection of black-and-white photographs sketching Samarkand in early 20th century. At that time, the medieval Samarkand is left in a terrible state of neglect and dereliction.

Bibi-Khanym mosque

A bit further east to the Registan, Bibi-Khanym mosque (replica, original 1399-1404) was meant to be Timur’s main architectural achievement in Samarkand and one of the biggest mosques in the world. Named after Timur’s Chinese wife, the ambitious building reaches the limits of construction techniques of its time. After a slow decay, it partially collapses in a 19th-centurye arthquake before its reconstruction in the 1970s.

My visit to Bibi-Khanym mosque is of blitzkrieg type, as my attempts to imagine the medieval life around and within the enormous outer and inner spaces remain unsuccessful.

Registan market

Samarkand’s main medieval market is no longer bustling on the Registan plaza. I visit the open market near Bibi-Khanym mosque again and again during my three-day stay in Samarkand, tracking there the legacy of the medieval trade. This is what I find.

Buses and mobile phones left aside, many elements above echo probably Samarkand’s medieval trade. Bright colours, strong smells, loud noises. Many people; multiple ethnicities, both genders, various ages, diverse social conditions.

The market is run all day long with hustle and bustle, trading mainly staple food. Clothing represents another major commodity. Dozens of female traders sitting in line, selling the same items than their neighbours to facilitate the customer’s choice.

Time to return to my hostel, after a long and rich day. But it is not over…

Gur-e Amir mausoleum

… Gur-e Amir (‘Tomb of the King’ in Persian language) is built early 15th century by Timur. The edifice is not completed until his sudden death in 1405 during a military campaign in Kazakhstan.

Initially buried in Kazakhstan because of the winter, his sarcophagus is brought later to Samarkand. In the mausoleum rest nowadays not only Timur but also his two sons and two grandsons including the unfortunate Ulugbek.

As my hostel happens to be located next to to the mausoleum, which I pay an evening visit to the monument. Despite the strong electric-blue and golden yellow colour casts, the mausoleum perspires a solid and appropriate sense of dignity and solemnity.

On my second day in Samarkand, I venture into more remote locations in the old town, only to confirm my interest in medieval Islamic architecture and street life.

Hazrat-Hizr mosque

I start my day with the small but beautiful Hazrat-Hizr mosque perched on a hilltop of Samarkand. The original 8th-century edifice is burnt to ashes by Genghis Khan five centuries later. Rebuilt only in the 19th century, the mosque is restored in the late 20th century by a private donor. I wish I could stay more, but other places call me insistently.

Shah-i-Zinda

Shah-i-Zinda (‘The living King’ in Persian language) is a fascinating avenue of Islamic mausoleums built between 11th and 19th centuries on a hill of Samarkand. Kusam ibn Abbas, cousin of the Prophet, would be buried there, after having contributed to the islamisation of the region.

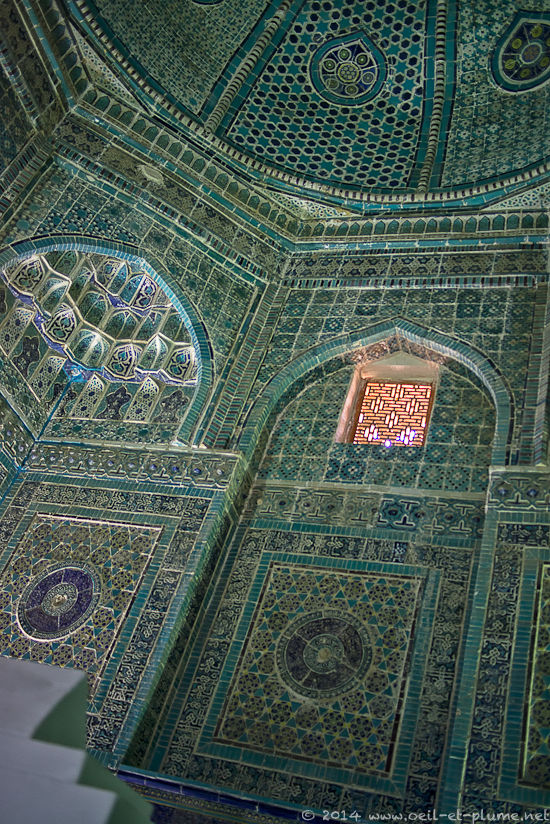

Resting place of a sister and niece of Timur, the emerald-green interior of the Shodi Mulk Oko mausoleum (14th century) strikes me by its beauty. In fact, all monuments do so with their distinctice shapes and colours. Mystical atmosphere in which resting and living people’s connect.

I find my way out through the graveyard neighbouring Shah-i-Zinda. So many beautifully carved and graved tombs, as those contemporary monuments would challenge the classical beauty of medieval architecture.

Former Jewish quarter

Old Samarkand is much more than the medieval monuments depicted above. Unlike Bukhara, Samarkand intends to seal off the less touristy areas to the traveller. Not for me. I found my way into various neighbourhoods of the former Timuran capital to feel the real life of the local population.

Beside the neighbourhood behind Gur-e-Amir mausoleum, I spend hours and hours strolling the colourful and tasteful old Jewish quarter. Once, a bystander indicates me spontaneously the direction of the old synagogue. While thanking him for his kind initiative, I can only laugh and tell to in my inner self: ‘I did not come to visit the synagogue, guys, I came for you’.

Each photograph below could be worth of a story. This is not appropriate here. Just imagine yourself the social encounter.

Doubtful? Consider the following scene, for instance. I spot this girl carrying her sweet doll on a street under the harsh midday sunlight. She walks fast because lunch is ready and mom is waiting for her. However, she forgets about her lunch and waiting mom when she realises my presence and my photographic equipment.

Our little girl urges me to pose for me with her favourite doll, what I gladly do. Bent on my shoulder in the middle of the street, she inspects carefully her digital portrait. All of the sudden, she rewards me with a loud and long kiss on my cheek to express spontaneously her satisfaction before running home, happier than never…

I walk away, a bit more than embarrassed in front of the bystanders. Only to document the following picture soon after.

Charming Bukhara, lovely Samarkand.

Cheers,